Explodapedia: The Brain

Ben Martynoga, illustrated by Moose Allain

David Fickling Books

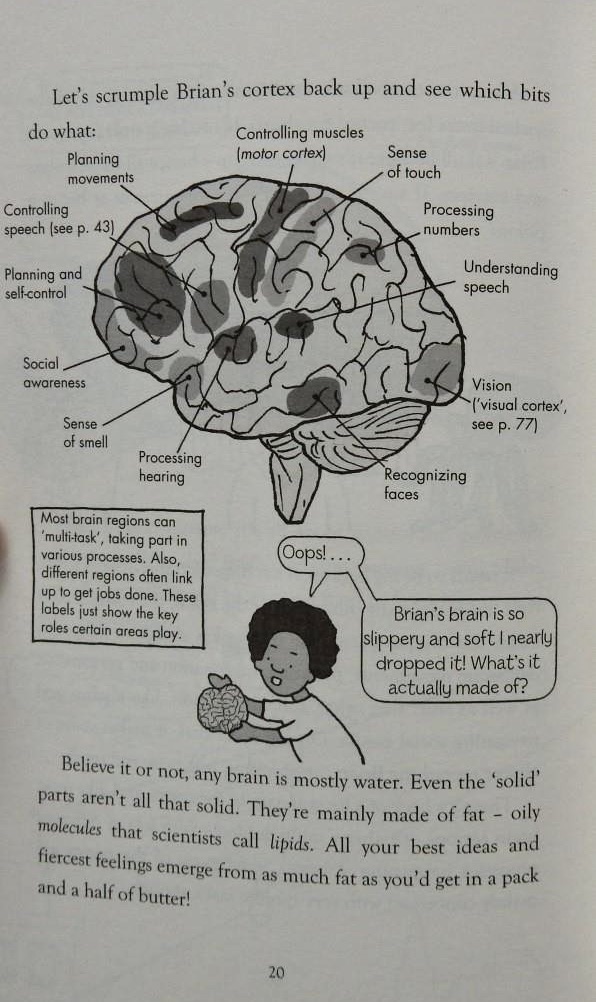

This is the fifth in the excellent Explodapedia series by neuroscientist and writer, Ben Martynoga and illustrator/cartoonist, Moose Allain. These two are aided by a talking octopus – a creature with nine brains and a rather high opinion of itself – and a human boy, Brian who allows his brain to be removed temporarily and used as an exemplar. Brian’s brain is unique but in common with other people’s is made mostly of water and has 180 billion microscopic brain cells. In order to show how a human brain works, readers are then shown inside Brian’s where there are neurons – the information carriers – and glia which work with the neurons, thus keeping the brain going. A fully-grown brain contains around 86 billion neurons and about the same number of glia, linked it’s estimated, by 600 trillion synapses.

The next chapter introduces some of the scientists who came up with ground-breaking ideas about brain functioning starting way back with doctor and scientist, Hippocrates who lived in ancient Greece around 400 BCE. We also learn of contributions made by Galen, (Rome 170 CE), Vesalius (1540 CE), Descartes (Paris 1640 CE) famous among other things for his ‘Cogito ergo sum’ – I think, therefore I am. Moving nearer to the present time comes the mind-reading done by Dr Thomas Oxley and team who inserted a brain-computer interface (BCI) close to the motor cortex of the cerebral cortex that controls movement. This enabled a patient with motor neuron disease to operate his computer by mind control instead of his hands, which he was unable to move. How amazing is that.

Rather than discussing the remaining seven chapters I’ll just say they explore in order, What brains are for, illusion or reality wherein is an outline of an experiment that had participants plunging their hands into painfully cold iced water with some being told to swear aloud when their hands started hurting and the rest told to stay quiet. Apparently the former felt less pain because swearing can trigger the production of natural ‘painkiller’ chemicals within the brain – fascinating. Then come how brains change from infancy to old age, all the different ‘yous’ inside your head, the conundrum of consciousness and how it affects decision making. The penultimate chapter looks at differences in people’s brains and includes developmental conditions – neurodivergence, depression, anxiety disorders and addiction. The brains of other animals is the topic of the last chapter and the book concludes with a look to what 2075 might have to offer; there’s also a very useful glossary.

Once again Ben Martynoga demonstrates his brilliance at taking key concepts and making them accessible, fascinating and entertaining. Matching the author’s quirky, witty style are Moose Allain’s illustrations, making this book even more readable with a wealth of speech bubbles as well as clear diagrams. Expand your mind: join them on a journey of wonder and discovery.