Moving the Millers’ Minnie Moore Mine Mansion

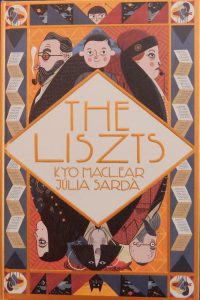

Dave Eggers and Júlia Sardà

Walker Books

This non-fiction story begins back in the 1870s when a dog belonging to a prospector was digging in the ground and found not the gopher it had been chasing, but silver. This discovery very soon became Minnie Moore Mine. Several years later the mine was sold to an Englishman, Henry Miller, making it Miller’s Minnie Moore Mine. It made him extremely rich. He found a wife, packed her off to Europe for a while, giving him time to build a riverside house they would share on her return – Millers’ Minnie Moore Mine Mansion. There a son was born to the couple.

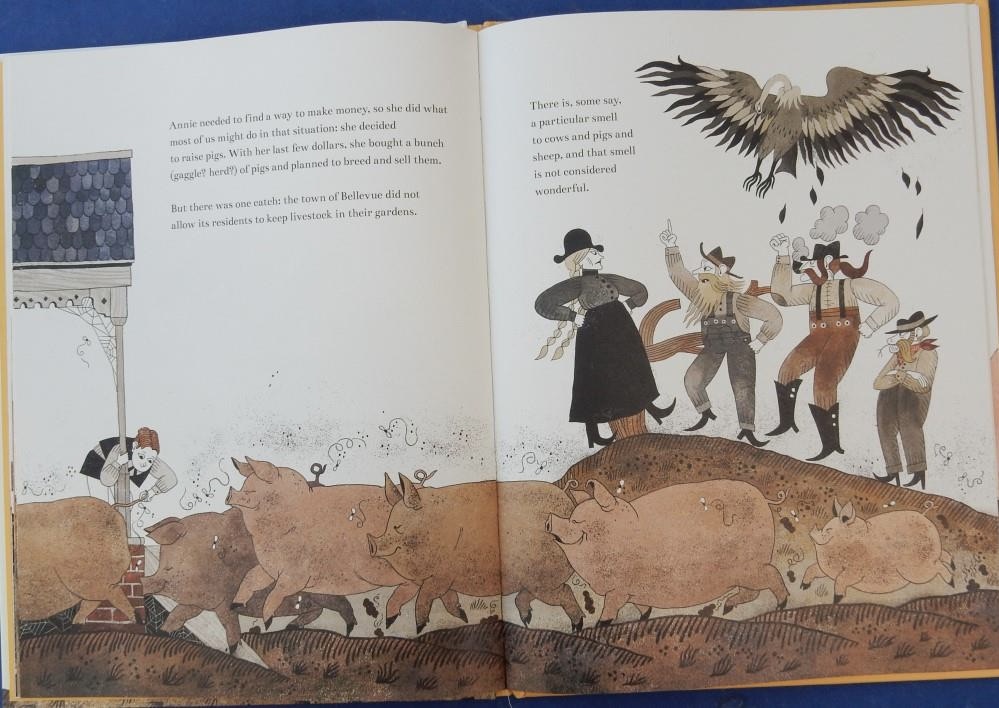

When Henry died his widow, Annie was tricked by a crooked banker to invest her money in his bank; it failed and she lost almost all of it. With the little left she bought some pigs intending to become a breeder. However the Bellevue townsfolk would have none of it

so our enterprising Annie devised a plan – a pretty elaborate one – to move the house out of town. And so she did. Aided and abetted by her son and some hired workers, Millers’ Minnie Moore Mine Mansion was shifted just four miles down the road,

where without pig restrictions, Annie, Douglas and the porcine team thrived for many years.

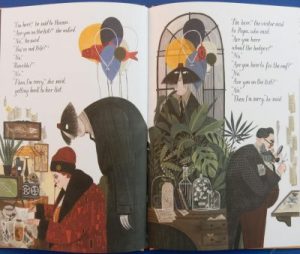

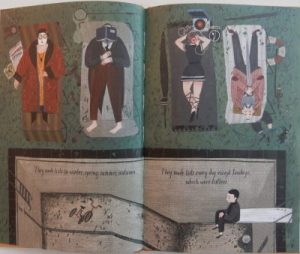

Crazy but true, though if you want to know how they managed to move, you’ll need to get your trotters on a copy of Dave Eggers and Julia Sardà’s book. The former’s chatty, humorous writing style and droll, often dramatic art rendered in earthy tones by the latter show how human perseverance and resourcefulness win through on several occasions.

Slightly bizarre, this would make an entertaining read aloud.