Ranger Hamza’s Eco Quest

illustrated by Kate Kronreif

Ivy Kids

It’s great to be back in the company of Ranger Hamza and here he takes three children and readers on an important learning journey to discover how nature’s everyday heroes from the smallest seed to the tallest tree play a crucial role in our ecosystem, and how we also have a vital role to play. It’s not difficult and Ranger Hamza explains in straightforward steps some ways to help the planet, starting with the making of a mini water butt.

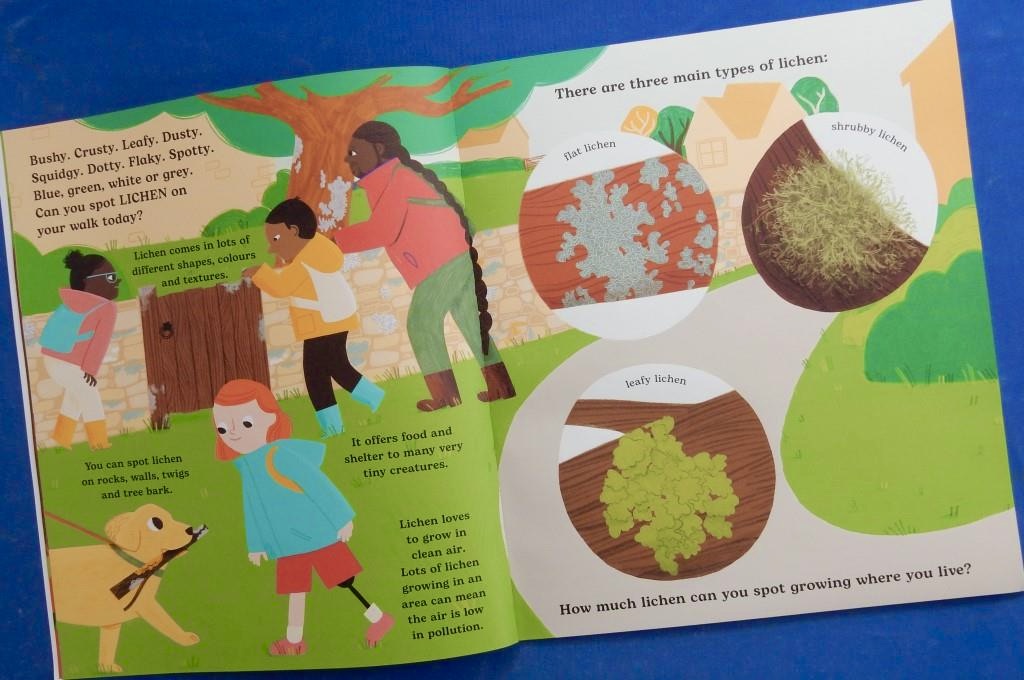

I loved the adjectives used to describe lichen, of which there are three types. In addition to providing food and shelter to tiny creatures, lichen acts as an indicator of the air quality in an area: lots of lichen indicates the likelihood of low pollution, so next time you walk with children keep a watch too see how much is growing.

One thing virtually everybody will notice is dandelions; rather that pulling them up (even from your garden), leave a place where some can grow. In so doing you will be helping several kinds of insects. I know from experience that children love to plant sunflower seeds and watch them grow: this is a great way to provide food for birds, so long as you keep the heads, let them dry out and then put them somewhere birds can access.

These are just some of the suggestions in this thoroughly engaging, inclusive book. It’s never too soon to start teaching children about ways they can help nature thrive so I suggest adding a copy to your family bookshelves, and foundation stage/ KS1 teachers, you need one in your classroom: it offers an abundance of forest school activities.

Another highly effective narrative non-fiction book is

Brown Bears

Dr Nick Crumpton, illustrated by Colleen Larmour

Walker Books

Set in Alaska, USA, this tells the story of a mother brown bear and her two cubs, one male, one female that we follow through a year in the forest. Therein lie dangers aplenty so, almost as soon as they are born, the mother bear starts teaching her offspring survival skills in order that they will be able to live and thrive alone in the wilderness.

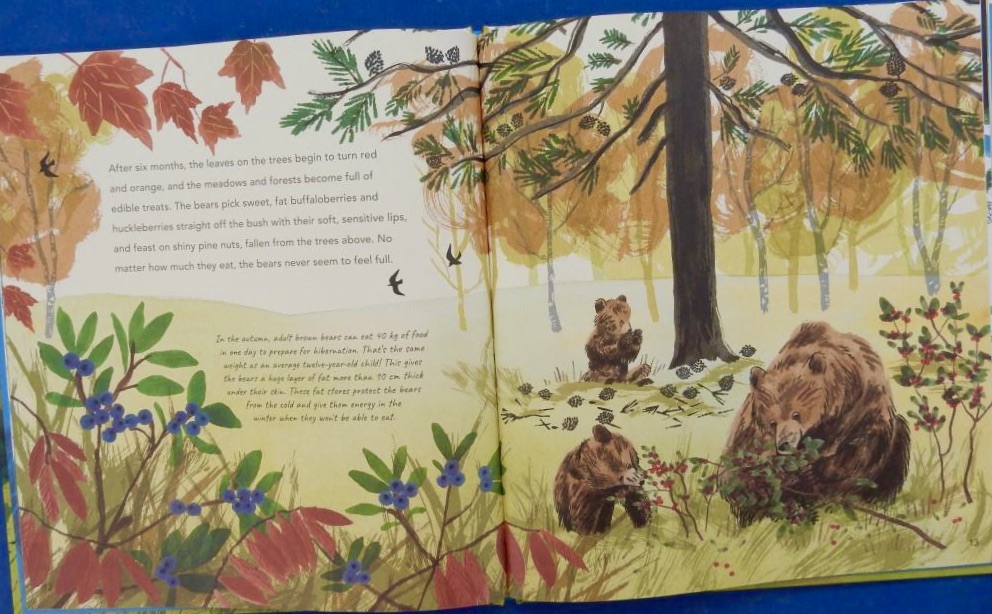

The cubs learn to climb, to leave scents to inform other bears where they’ve been and to remove bugs from their skin. It’s dangerous for bears to stay too long in locations where people have left discarded food, as this can endanger both humans and the bears that have followed their noses. Much better is picking berries and foraging for nuts in the meadows and forest areas, which is what the cubs do come the autumn to build up a layer of fat to help protect them through the winter when hibernation prevents them from eating.

Come the snowfall, mother bear builds a new den wherein they will all spend the winter, in the warmth trapped by the tree branches covering the tunnel’s entrance.

After a whole seven months the mother wakens as do the cubs, the light hurting their eyes after so long. Then it’s out into the melting snow to start feeding again and come the summer part of their food will be salmon that have come to lay eggs in the gravelly rivers. Danger isn’t over however; indeed it comes in the form of a massive, very hungry male brown bear; but thanks to the cubs’ climbing skills and their mother’s warning sounds, the three remain safe and as autumn approaches again, the male cub will leave his family and go in search of a new home

Beautifully illustrated and captivatingly written, (with paragraphs of additional information to enjoy either during or after reading the main narrative), this is perfectly pitched for KS1 children.